Music expert Mark Gotham about finishing Beethovens unfinisched symphony supported by artificial intelligence.

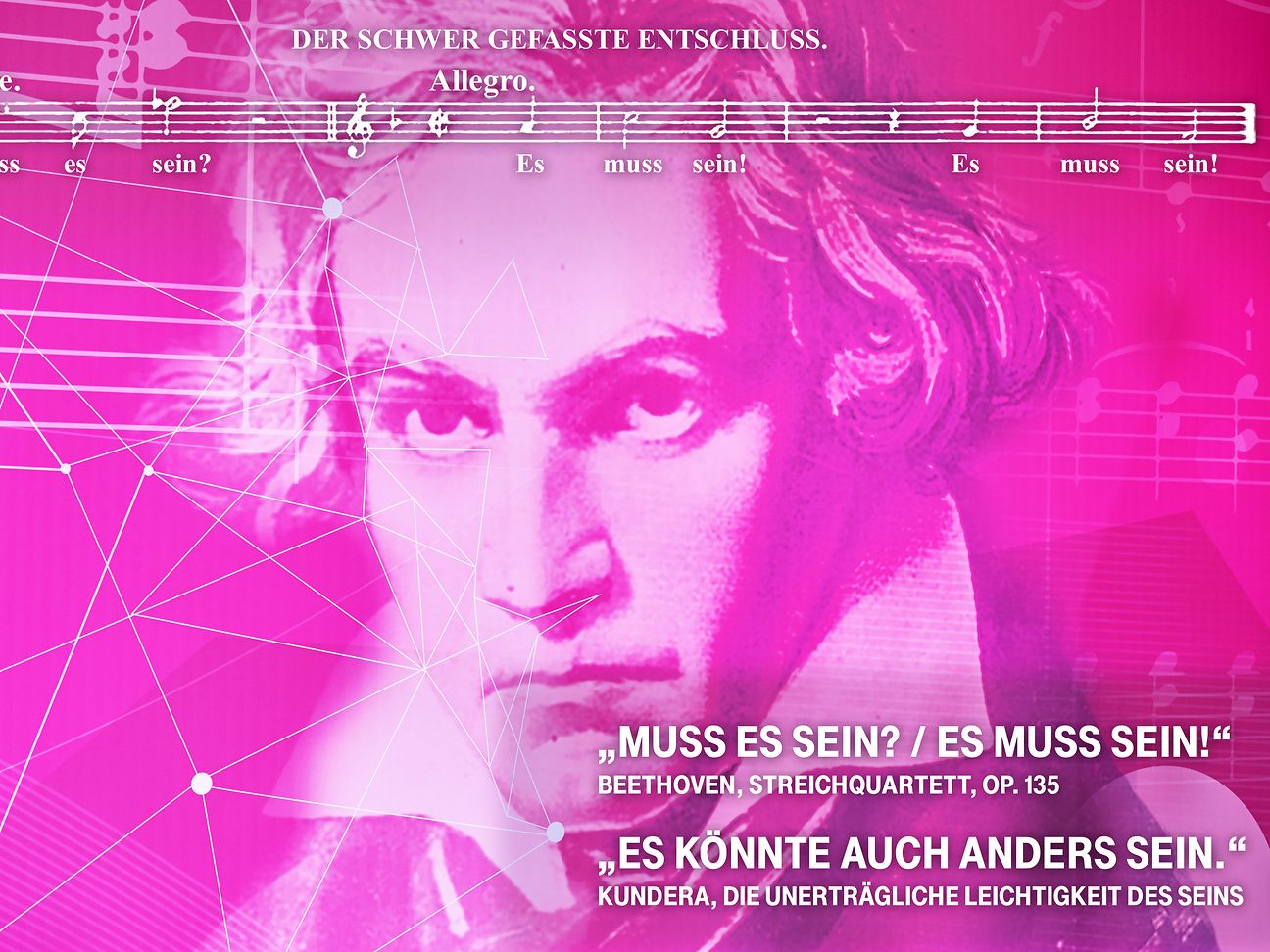

For many good reasons, we have inherited an image of Beethoven as an intensely focussed, uncompromising visionary. There are many iconic stories, quotes and moments to motivate this impression, not least of which is the tantalisingly cryptic ‘Muss es sein? / Es muss sein!’ (Must it be? It must be!) Beethoven penned on one of his very last, substantial compositions (the String Quartet No. 16 in F major, Op.135 of 1826).

There’s been great speculation about ‘what’ exactly it is that ‘must be’ ranging from the distinctly quotidian to the most elevated existential pondering. On the specific end, it seems most likely that Beethoven had an over-due payment he was owed in mind (and Beethoven certainly had no qualms about including such mundane matters right at the heart of his loftiest music!). At the other extreme, those specific answers do not stop commentators from seeing in Beethoven’s ‘muss sein’ a neat encapsulation of his revolutionary spirit. Does the piece have to go this way? Must it have such challenging, radical compositional developments? Yes, it must!

But it can be misleading to see Beethoven’s compositional output as a series of ‘muss sein’s. It may seem inevitable that pieces like the Fifth Symphony or Für Elise would end up as they did; it can be jolting to imagine alternative options and variants for such well known music. But this fixed view can sideline the Beethoven who improvised, who was spontaneous, even witty. Beethoven’s sketches remind us of this alternative viewpoint. If they teach us anything, it is that his creative process involved many options, changes of mind, and paths untravelled. Milan Kundera takes up this motif (obliquely) in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, pondering the idea that ‘Es könnte auch anders sein’ (It could be otherwise).

These kinds of questions loom large behind efforts to understand Beethoven creative process, and especially behind efforts to ‘complete’ unfinished work. Is there a single correct answer or a set of equally credible options? How are the boundaries to these possibilities defined?

This exploratory project asks what the latest developments in machine learning might bring to bear on such a task. More specifically, to ask what AI is capable of in the domain of automatic music completion in general, and what forms of human-AI collaborations might be possible and profitable to make best use of all the expertise and resources available.

Beethoven’s 10th symphony provides a fertile testing ground for such a task. There is a small amount of surviving sketch material which is relatively robustly associated with this work: this provides enough to give the project some significant points of departure, but it is sufficiently scant for most scholars to have determined that the work cannot be completed by traditional means. It is compelling to think that with human guidance, machine learning might be able to make a lot out of a little, bringing the realisation of works like this into the realm of the possible, the ‘könnte sein’.

The collaborative element is key here. One does not simply press a button and get a new Beethoven symphony. We need judiciously selected goals paired with careful implementation and curation to make the most of Beethoven’s sketch material for this work, of the computational processes available, and of the evidence to be had from other relevant music that Beethoven wrote or knew.

There will come a time when the machine-learning system can integrate all the information we know to be important, working directly with Beethoven’s entire body of sketches as well as the completed works to ‘learn’ his compositional process. Exciting, emerging projects like the ‘Beethovens Werkstatt’ prove that at least a form of this is eminently realizable, suggesting that the necessary, structured representation and parsing of this information will indeed be available to future versions of this project, perhaps in around 10 years’ time.

In the meantime, we need to start with old-fashioned sleuthing through the archives in order to find and encode ‘seed’ material for the machine to work with. So the story begins with some very traditional musicology — the parsing of Beethoven’s notoriously ambiguous sketches.

This blog series will attempt to shed some light on all of this, starting with a mini-series on ‘musicological expositions’ and returning in due course with ‘data-driven developments’ and ‘compositional recapitulations’. In these ‘Musicological Expositions’ we’ll look at the few hints which Beethoven’s sketch materials provide, focusing our attention on two new contributions which move the prospect of a completion forwards: one re-reading of a known sketch, the other on the emergence of an additional ‘pseudo-sketch’.