Inside of CL0P’s ransomware operation

TA505 (also known as FIN11) is a financially motivated cybercrime actor. They conduct Big Game Hunting operations, such as deployment of ransomware and extortion of large ransom payment. In the past, I explained how they operate and I scrutinized their tools. If you are not familiar with TA505 and CL0P then I recommend you to read our threat actor profile of TA505 first.

Three waves of spam originating from TA505 were observed in 2020: they started in January/February, followed by a longer period during summer from June until September, and a very short period in early December. Throughout the months without spamming activity, they added more and more victims to their ransomware portal “CL0P^-LEAKS”.

This blog post gives insights into their ransomware operations. First, I’ll detail the activity of these operations throughout the last months. Next, I’ll describe what kind of victim information CL0P samples contain and explore why there are often multiple CL0P samples that can be attributed to one victim. Finally, I’ll have a look at their two online portals that support their operations: their leak portal “CL0P^-LEAKS” and their negotiation portal that they utilize to come to agreements with victims.

Our Incident Response Service at Deutsche Telekom Security GmbH can quickly investigate and remediate ongoing TA505 intrusions. Please contact security-info@t-systems.com for more information.

TA505 and CL0P operations from June 2020 until December 2020

In the following, I’ll give an overview of TA505’s activity during the second half of 2020. There were two periods of spamming activity, followed by two periods of CL0P deployments.

First activity period

The first period of spamming activity began on 2020-06-02 and ceased on 2020-09-11. During this period TA505 sent out phishing mails nearly each work day in order to get a foothold in many networks. Subsequently, they would filter down on interesting corporate networks and then they would advance their intrusion by moving laterally.

The end date of the observed spamming activity is particularly interesting due to an announcement of Secura. On 2020-09-11, which was a Friday and therefore, the last day of a typical TA505 spam week, Secura announced the Zerologon vulnerability. It is only speculation why TA505 did not continue its spamming activity on the next Monday: either it was the publication of Zerologon that ended their spamming activity abruptly or they grasped the opportunity to quickly move laterally in selected networks.

In September and October 2020, CL0P was able to deploy their ransomware at several victims. The observed cases took mostly place on Friday and Saturday.

Second activity period

In mid-December 2020, TA505 returned for less than two weeks of spamming activity, likely to compromise possible victim networks for CL0P deployment during the Christmas holidays 2020. Another motive might be to acquire access to new victim networks in order to resume operation in January / February 2021.

As of time of writing, there are no new victims listed on their leak portal “CL0P^-LEAKS”. However, I found several CL0P samples indicating at least that the CL0P operators tried to deploy their ransomware in two networks during Christmas. There are rumors that one of these victims payed more than 200 Bitcoins (BTC) (almost six million dollars) ransom.

CL0P ransomware

CL0P is the ransomware that is deployed after initial TA505 intrusions. Each CL0P sample is unique to a victim. First, it contains a 1024 bits RSA public key used in the data encryption. Second, it contains a personalized ransom note.

The ransomware is written in C++ and developed under Visual Studio 2015 (14.0). So far, I’ve only observed CL0P samples for the x86 architecture. The unpacked sample size is between 100 KB and 200 KB. CL0P renames encrypted files and adds either the “.Cllp” or the “.CI0p” file ending.

The ransomware contains a 1024 bits RSA public key, which is unique to each victim. While 1024 bit RSA keys are deprecated, factoring of 1024 bit keys is still quite far away. As of January 2021, the largest publicly known RSA key that was factored as part of the RSA Factoring Challenge had 829 bits.

There is already a good write-up of CL0P’s functionality from S2W LAB. Therefore, I’ll refrain from describing how CL0P encrypts a system. Instead, I’ll look into how it decrypts its embedded ransom note and cases where there are multiple samples that can be attributed to a victim.

Decryption of embedded ransom note

Each CL0P sample contains a ransom note, which is stored as a resource in the PE executable. Across several CL0P samples the resource string 0x99AB and the resource type ID_HTML were consistent. This resource is a binary blob that is encoded with a XOR cipher. Each sample contains a 33 bytes long hard-coded XOR key. As of time of writing, I came across two different keys that the CL0P operators reutilized across several samples.

The following screenshot shows the function responsible for storing the ransom note. Its only parameter is the path where to store the ransom note. The name of the ransom note is hardcoded (“README_README.txt”). First, this function builds the full path of the ransom note and tries to create a file (lines 15 – 17) there. On success, it fetches the resource with name 0x99AB and reserves memory for the decrypted ransom note (lines 19 – 25). In a for loop each byte of the encrypted ransom note is XORed with a byte from the hard-coded XOR key. This key byte is determined using the position of the current byte modulo the size of hard-coded key, which is 33 bytes (lines 26 – 27). Afterwards, the function stores the decrypted ransom note and cleans up (lines 28 – 37).

This note is specifically crafted for the victim. Let’s have a look at a redacted ransom note that a recent CL0P sample dropped:

To reiterate what this ransom note comprises:

- The name of the victim

- Information about sensitive data they exfiltrated

- File share paths

- User names as part of these paths

- The amount of data they exfiltrated

- A .onion link to their leak portal “CL0P^-LEAKS”

- Several email addresses to contact

- A link to their negotiation portal

Firstly, these are sensitive information about the victim. Secondly, this is information to interact with the CL0P operators. Therefore, it is recommendable to never upload ransomware samples to the Internet.

Given the ransom note an attribution to a victim is possible. In the following, I’ll use this to investigate a very interesting trial and error behavior observed during CL0P intrusions.

Trial and error: Why are there several samples per victim?

During the last three months, I could find more than a dozen CL0P samples on VirusTotal. In multiple occurrences, there are several samples of CL0P that can be attributed to one victim. These samples are compiled within a time frame of a couple of hours. In at least one incident response engagement, we could corroborate this behavior as well.

The question arises why are there several samples per victim? In the following sections, I’ll investigate the cases of four CL0P victims where multiple samples can be attributed to the same victim. The attribution to a victim occurs based on two data points. First, CL0P samples comprise a ransom note that mentions the victim name. Second, I consider CL0P’s time stamps legitimate. This is in line with what we’ve seen in several incident response engagements.

Victim A

The case of victim A occurred on a Saturday during Autumn 2020. Both samples were compiled on the same day within 30 minutes. The following table lists important properties regarding both samples:

The first deployment of CL0P failed since the endpoint detection blocked Sample 1. As a consequence, they compiled Sample 2. They changed the service name that CL0P registers as well as the mutex name it uses to ensure that not more than one instance runs on a system. Furthermore, they exchanged the functionality to deal with McAfee antivirus. The operators defaulted to functionality to deal with Appcheck, which was already observed in December 2019.

Interesting is that the first sample is signed with a (now) revoked certificate but the second sample is not signed. Either the operators forgot to sign of the second sample after the compilation or the signing is carried out as a service by another entity and the operators did not bother to sign the second sample.

The case of victim A shows that the CL0P operators adjust their ransomware in a trial and error fashion during the deployment stage. This may give us some hints regarding the relationship between the operators and developers of CL0P.

We can spin up several hypotheses. Either the operators and developers are the same, or the operators work very closely with the developers who assist with recompilation during the deployment stage. Another hypothesis is that the operators have access to the source code, they are capable of changing the source code, recompiling it, and finally deploying the new binary. This is not typical behavior seen by actors working as part of a Ransomware-as-a-Service program.

Victim B

The case of victim B took place during a Saturday in November 2020. Both samples were compiled on the same day within 15 minutes. I list the relevant properties of both samples in the following table:

Sample 1 is not capable of encryption. The CL0P operators changed the WinMain function of this sample so that instead of encrypting the system, it runs a long sequence of ShellExecuteA calls in order to kill several processes and stop several services. The following screenshot shows a portion of the decompiled WinMain function.

Since the CL0P operators compiled Sample 1 with most of the WinMain logic replaced by ShellExecuteA calls, there is a lot of dead code and unreferenced strings, respectively. For instance, the service name and the mutex name strings are stored in the binary but they are never created.

Sample 2, which was utilized to encrypt the infrastructure is fully working. It does not comprise any functionality to cope with antivirus products. This is what Sample 1 (probably) achieved. The same service name was utilized but they slightly changed the mutex name by prepending another “666” to the mutex name string.

Again, Sample 1 is signed with a (now) revoked certificate but Sample 2 is not signed.

In the case of victim B, the CL0P gang encrypted the network but they did not achieve their objective of being paid a ransom.

Victim C + D

The cases of victim C and victim D happened during the Christmas holidays 2020. Both cases occurred during the same day. All three samples that I’m aware of were compiled on the same day within seven hours. The following table summarizes important properties of them:

In case of victim C, I could only find one sample (Sample 1) and I am missing the second one (Sample 2). The CL0P operators compiled Sample 1 again with a long sequence of ShellExecuteA calls to kill services / stop processes. This includs several security solutions like McAfee and Sophos. Sample 1 does not conduct any encryption of files as it exits after the ShellExecuteA calls. Again, there is a lot of dead code but this time there is neither a service name string nor a mutex name string to be found. Unfortunately, I was not able to encounter Sample 2, which supposedly encrypted Victim C’s infrastructure.

As of time of writing, Victim C is not listed on CL0P’s leak portal. Therefore, we can suppose only two things: either this was a failed intrusion and the ransomware was never rolled out because something went wrong during the deployment of Sample 1 or Sample 2. Or the CL0P operators deployed Sample 2 successfully, victim C paid the ransom, and is therefore not listed on the leak portal.

In case of victim D, I found two samples. Both samples were compiled on the same day but within six hours. Both samples comprise the ransomware logic. The semantic capabilities of both samples are almost equal. The difference between Sample 3 and Sample 4 is not as clear as in the cases of victim A and victim B, though.

In contrary to victim C, we’ve got clear indications letting us assume that CL0P achieved their objective of successfully encrypting victim D’s infrastructure.

CL0P’s online presences

CL0P maintains two online presences to support its Big Game Hunting operations. The first presence is their leak portal called “CL0P^-LEAKS”. Its purpose is to frighten future victims by hosting sensitive data of past victims that didn’t pay the ransom. The second presence is their negotiation portal. This serves as a “customer support” for victims that are willing to come to an agreement and pay the ransom.

Victim intimidation: CL0P’s leak portal

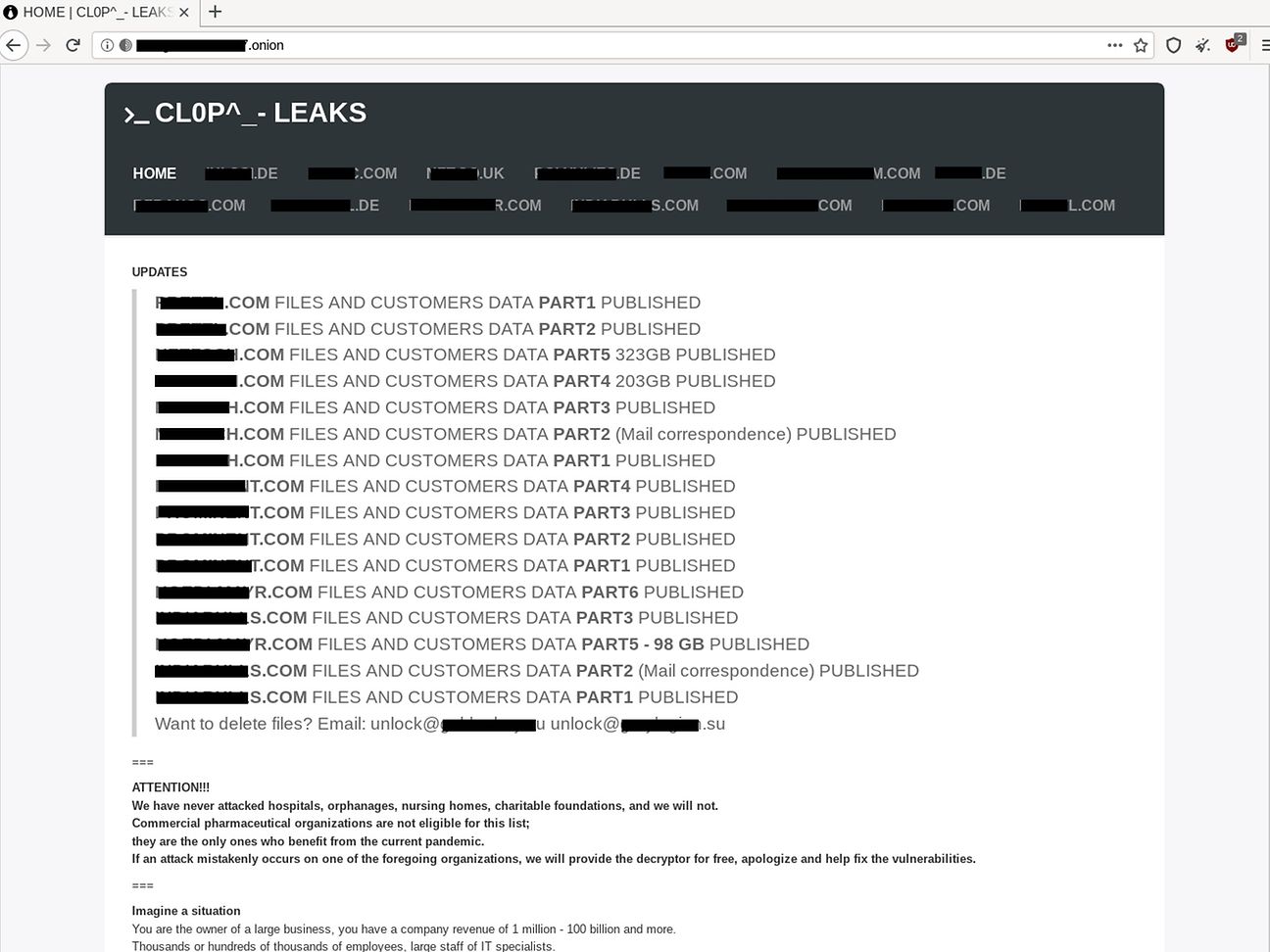

CL0P is one of the ransomware gangs that adopted the double extortion technique. Before they deploy their ransomware, they exfiltrate up to terabytes of sensitive data from the victim’s network. In case the victim had proper backups setup and is not willing to pay the ransom, they still can threaten to publish this data on their leak portal “CL0P^-LEAKS”. The portal lists 19 victims in January 2021. The majority of them residing in Germany. The following screenshot shows their leak portal hosted on the TOR network:

In comparison to other ransomware gangs, CL0P is very ruthless. In some cases, they host terabytes of very sensitive data of their victims for months on their leak portal. The CL0P operators added the first victims in Spring of 2020, which they are still hosting after 9 months.

As stated before, CL0P is going after the data of top executives. Several of their recent ransom notes explicitly name data stolen from workstations that belong to top executives (including founders / CEOs) of the respective enterprises. This is likely based on the hope that using data stolen from top executives in the extortion process raises their chances that the victim pays. Nevertheless, they still exfiltrate data from network shares (e.g. finance / human resources data).

Victim support: CL0P’s negotiation portal

The sustainability of CL0P relies on victims paying the ransom. Based on their continuous operation one has to assume that a good portion of the victims agree to pay the significant ransoms. Apart from their leak portal “CL0P^-LEAKS”, they offer a negotiation portal for every victim. This is their tool to come to an agreement with victims that are willing to pay.

As of time of writing, the ransom note comprises the link to this portal. I was able to extract the ransom note from several CL0P samples. The ransom notes show that a separate .onion link is created for each victim. The following screenshot shows their negotiation portal and the services it offers to their victims:

These services are:

- Chat: a support chat where the cybercriminals guide the victims through the negotiation process

- Demo decrypt: a decryption tool that victims can use to decrypt up to five files of their choice

- Buy bitcoin: information on how to buy bitcoins

- News: colorful screenshots of news related to CL0P’s latest cyberattacks

- About us: further links about them

The CL0P operators try to convince their victims to pay by showing off their history of hacks in a colorful way (Section “News”). Links to third-party websites (Section “About Us”) give more background information on them.

The negotiation process follows the same pattern as with other ransomware gangs. The tone of the conversation is helpful and direct but never hostile. First, they ask if their interlocutor is authorized to negotiate and mention that they are just interested in the money.

Our goal is money, we are not interested in causing harm. We tell you the amount we want to receive for unblocking the network and deleting all the files that we have downloaded from you. We come to an agreement and after receiving the money, you receive a decryptor and proof of file deletion.”

If both parties come to an agreement, then the CL0P operators provide a decryptor and a proof that they’ve deleted all exfiltrated files. In exchange they want money in bitcoin. They offer the free decryption of up to five non-critical files to prove that they can decrypt the victim’s network and to show the victim their good will.

They demand amounts of 5% to 10% of the annual revenue but they tell victims that discounts of up to 30% are possible, if they come to an agreement within less than a half week. Nevertheless, they are open to further bargaining so that the final ransom is way less than the initial demand of 5% to 10% of the annual revenue.

Once both parties agreed on a price, the CL0P operators offer further support and suggestions on how to make transfers in Bitcoin. They are willing to accept small fluctuations due to Bitcoin. Though, they know that Bitcoin fluctuates a lot and they only fix a ransom for 24 hours.

After they received the ransom in their Bitcoin wallet, they still continue their support. Victims are typically very concerned about three things. First, what data CL0P was able to exfiltrate and that they receive a file deletion report. Second, they require further support to decrypt their infrastructure. Third, they want a report on how the network breach happened. The CL0P operators seem to help victims with these issues even after they’ve already been paid.

Conclusion

CL0P was one of the most active Big Game Hunting operations in 2020. They were able to breach several large enterprises. Their intrusions are linked to TA505. I expect that these intrusions continue with the same speed and frequency in 2021.

CL0P samples comprise personalized ransom notes that mention the victim and give away crucial details about the negotiation process. The CL0P operators offer their own portal for negotiations, including a support service via chat.

In cases where victims do not pay the ransom, they upload large amounts of sensitive data to their portal “CL0P^-LEAKS”. As of time of writing, they continue to host this data there, in some cases for more than nine months.

I documented the trial and error behavior observed during CL0P deployments: in several deployments there is more than one sample that is linked to a victim. In some cases, it seems that the first sample was an initial test whether or not the endpoint detection blocks the sample. In other cases, the first sample does not contain the decryption capability since the operators likely commented it out for this build.

This shows that the CL0P operators have access to the source code of CL0P. They are capable of compiling and quickly fixing issues in it during an ongoing deployment. This underlines the assumption that this ransomware gang is a closed group of individuals sharing mutual resources and working closely together.

Appendix A: IoCs

The following table lists network IoCs associated with TA505’s spamming activity in December 2020.