Smokeloader is still alive and kickin’ – A new way to encrypt CC server URLs

The malware downloader Smokeloader is one of the oldest malware families that is still in use today. A malware downloader is a typically small program that fingerprints a target system, downloads one or more additional malicious programs and executes them. Malware downloader forms part of the cybercrime ecosystem: there are cybercriminals that offer to distribute malware for other cybercriminals. They sell a number of installations for a couple of dollars, depending on several factors such as the geographic position of the target and its operating system.

Smokeloader emerged from the Russian cybercrime underground in 2011. Its developer “SmokeLdr” is known to be customer friendly and they quickly act on customer complaints. Smokeloader is a crime kit that comes with a prebuilt bot, a PHP-based command and control panel, and a user manual. In addition, cybercriminals can purchase more domains for the bot (the default is just one domain) or additional modules that enhance the capabilities of the main bot (e.g. DDoS attacks).

Throughout the years, Smokeloader gained more and more anti-analysis measures to hinder its profound analysis. A recent detailed analysis described a wide variety of obfuscation techniques including opaque predicates, checking for running analysis programs, and anti-hooking measures. One anti-analysis trick is indeed very effective to hinder a full dynamic analysis. Smokeloader resembles a Matryoshka doll: it comprises three layers of obfuscation with the third being the final layer carrying out malicious activities. Before the second layer hands over control to the third layer, it checks if the filename of the executed Smokeloader binary contains a certain string. If this string is not found, then the third and final layer will not be unpacked. Since the filename of a sample is often either randomized or its hash itself, this is a severe problem for sandboxes in order to come to a correct verdict.

Within the last ten years, the cybercrime underground has changed significantly. There are many new contenders such as Buer or Zloader, and Smokeloader has to stand its ground in order to maintain its market share. This may explain the above mentioned anti-analysis measures. But nevertheless the developer “SmokeLdr” has to continue developing their project and improving it.

In this blog post, I will have a look at a recent change in the way how Smokeloader stores and decrypts its Command and Control (CC) server URLs. Until recently this malware used the XOR cipher in a broken way and as a consequence its CC server URLs were trivial to bruteforce. Samples observed in November and December 2020 implement a fix for this problem. In the following, I will show way the old implementation was flawed and how “SmokeLdr” fixed it in recent samples.

Recap: Broken XOR Encryption of CC URLs

Smokeloader implemented a very weak way of encrypting the CC server URLs. N1ght-W0lf described this in detail. An example of this algorithm can be found in sample 91879bdd73625ac38c31fe5225310e92.

In a nutshell, the bot relies on a XOR cipher. It comprises one or more encrypted buffers with encrypted CC server URLs. Each buffer’s first byte is the length of the encrypted URL, followed by the encrypted URL itself, and a four byte XOR key. An encryption function takes each encrypted byte of the buffer, XORs consecutively each byte of the XOR key with the encrypted byte. Finally, it applies another XOR operation with a hard-coded one byte XOR key. Since XOR operations are associative, we can use this to our advantage.

Let’s assume we have the following encrypted buffer. The size of the buffer is 0x1C (highlighted in red). This is followed by 0x1C encrypted bytes (highlighted in light green). Next, there is the XOR key 0x1AD4EC24 (highlighted in dark green). Finally, there is a buffer of zeros that are actually not in the binary but only for illustration purposes. We will see later why they are quite helpful.

Let’s see how the first letter of the URL is decrypted. Remember that first Smokeloader consecutively XORs the first byte 0x8A with each byte of the XOR key (0x1AD4EC24) and then it XORs this intermediate result again with the hard-coded XOR key 0xE4. The following equations demonstrate this. I use the fact that XOR operations are associative, i.e. the order of the applications does not matter:

As you can see, in the end 0x8A gets decrypted to 0x68, the ASCII code of “h”. We can see as well that due to the properties of the XOR operation and the consecutive application of five bytes (four bytes XOR key + one hard-coded XOR key), the effective XOR key deflates to a just a one byte long XOR key (0xE2).

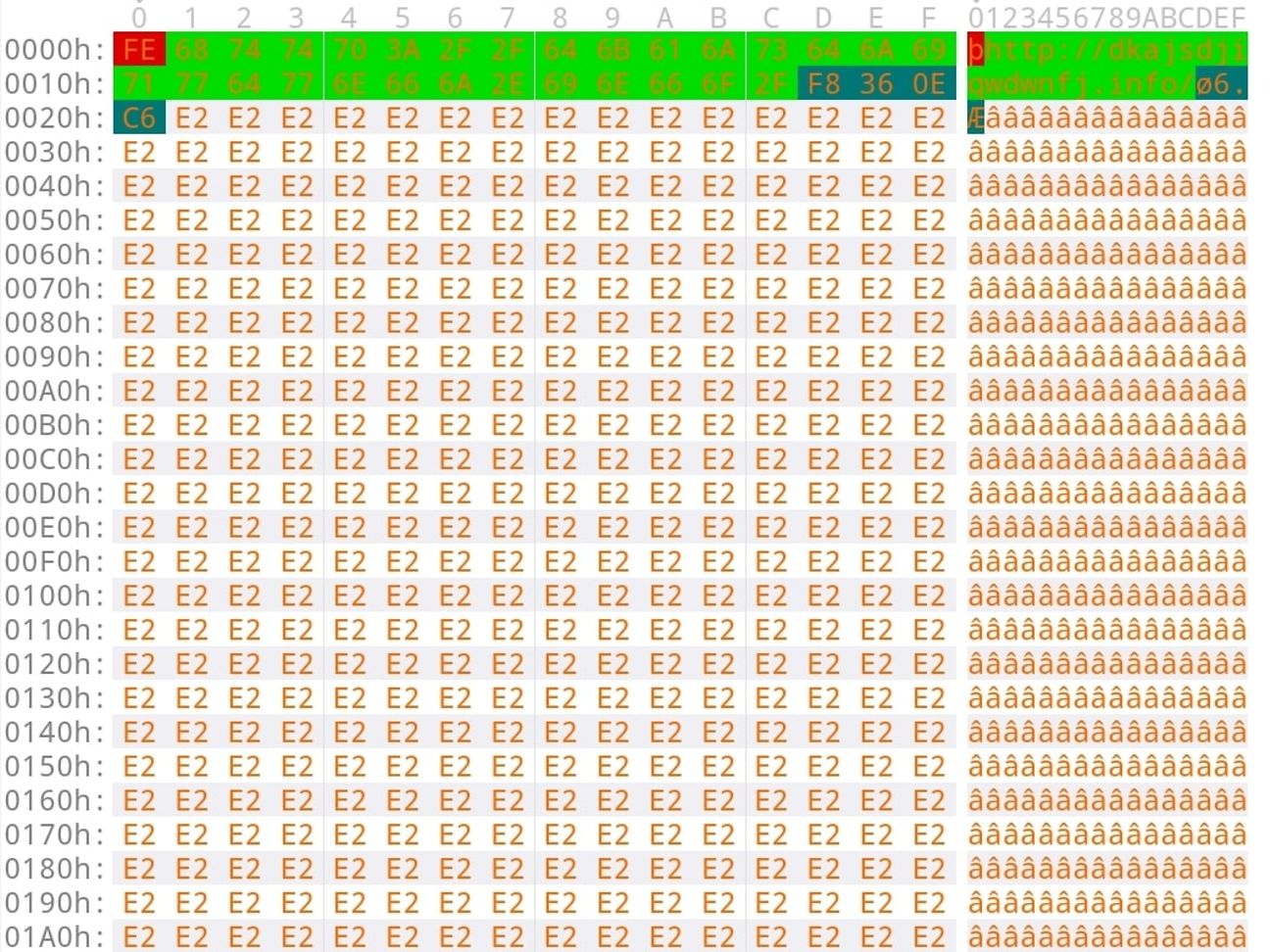

In practice, it was easy to bruteforce the deflated XOR key: XORing the whole unpacked binary with bytes in the range from 0x01 to 0xFF and looking for zero-terminated strings that begin with http was enough to find the CC server URLs. The following figure illustrates this. We can see the CC server URL (highlighted in light green). Note that the buffer of zeros now mirrors the deflated XOR key 0xE2 since each value XORed by zero will result in the original value.

Long story short: never use the XOR cipher as Smokeloader did in the past if you are serious about obfuscating (or “encrypting”) something. Consecutively applying several one byte XOR keys does not increase security. The final key will still be one byte and easy to bruteforce with just 256 possible keys to choose from.

Improved Obfuscation of Command and Control Server URLs

I’ve already mentioned Smokeloader’s continuous development in the introduction. Recently, I came across a Smokeloader variant (6e5017e2d0407e74578d1121233da979) that had an improved algorithm for obfuscating the CC server URLs. This improved algorithm mitigated the easy bruteforce decryption of Smokeloader CC server URLs.

The following figure shows an encrypted URL buffer as found in a recent Smokeloader variant. Again, the first byte is the length of the total buffer. But now the buffer is split in two parts. The first part is highlighted in purple and the second part is highlighted in light green. Finally, again, there is the four byte XOR key.

So how does Smokeloader compute the final decrypted URL? Have a look at the decompiled code of the CC server URL decryption function in the following figure.

First of it all, at its heart is still the old XOR cipher. But now it takes two buffers into account. The algorithm starts at the beginning of the first part of the buffer (purple). It fetches the byte at this offset and checks if it is zero (lines 27 – 29). If it is zero it sets the variable “is_second_part_buffer” to one and fetches a byte from the second part of the buffer (light green) (lines 31 – 32). If the byte of the first part of the buffer is not equal zero, the variable “is_second_part_buffer” will remain zero. Consequently, it XORs the fetched byte with the four byte XOR key (dark green) (lines 34 – 42). Finally, and this depends on the origin of the byte, one of two hard-coded one byte xor keys is applied (lines 43 – 47). In the example, bytes from the first part of the buffer are XORed with 0x66 and bytes from the second part of the buffer are XORed with 0xC9. If you compare the first part (purple) and the second part of the buffer (light green), then you will note that every time where a byte at an offset x is zero in the first part, it is not zero in the second part, and vice versa.

If you write code for configuration extraction, then you have to go the long way now since bruteforcing will not work anymore. This means that you have to first identify the function that decrypts the CC server URLs and extract the two one byte XOR keys. Next, you have to identify the encrypted URL buffer. First, you should extract the four byte XOR key. Then, you can join part 1 and part 2 of the encrypted buffer, while XORing with the correct one byte key. Finally, you can XOR the joined buffer with the extracted four byte XOR key, and voilà: we have our decrypted URL!

Next year Smokeloader will turn ten years old, let’s see how this cybercrime veteran will celebrate its anniversary…